Of all of the families who lost loved ones on 9/11, for some reason I only remembered one name. I had heard the stories and prayed with over 350 families, yet the only name I remembered was Clyde Frazier.

Of all of the families who lost loved ones on 9/11, for some reason I only remembered one name. I had heard the stories and prayed with over 350 families, yet the only name I remembered was Clyde Frazier.

The mayor’s office had decided to set aside a number of passenger ferries for the express purpose of escorting family members to actually see Ground Zero. After a short ferry ride the family members would walk to a staging area prepared for them.

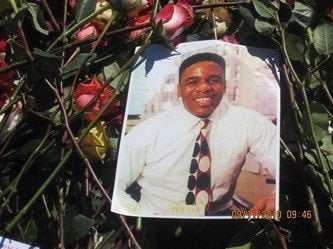

It was on the very first trip that I met Clyde Frazier Sr. When he saw the burning Pile he went weak in the knees and I truly feared he might be having a coronary. On the return trip he told me about this son Clyde Jr. The following excerpts are from an article by New York Times Sports writer Harvey Araton. He captured the essence of the man and the pathos of that first Christmas after 9/11.

Sports of The Times; Recalling The Assists From Clyde

By HARVEY ARATON

Published: December 25, 2001

OVERFLOWING with holiday cheer in recent days was the New York sports stocking, as Michael Jordan graced Madison Square Garden with another winning jump shot, the Olympic torch was placed in the guiding hands of Giuliani and Torre, and the Giants and Jets invigorated their playoff possibilities with late touchdown passes.

Yet this Christmas Day, far more than reception, is for reflection. It is for too many families to assemble one last time this cursed year, together but incomplete.

‘I sit here still dazed by the whole thing, by the loss of my son,’ a father says from his home in Queens. ‘If I had one gift to get for the rest of my life, it would be to have him back.’

The father’s name is strangely famous but he is not, and his story has become devastatingly common, post 9/11. Clyde Frazier lost the oldest of three sons at the World Trade Center. Clyde Jr., a state tax investigator, was 41. He worked on the 86th floor of the south tower, and his last words to a friend via cellphone — minutes before his building was hit — were: ‘Gotta go. . . . Gotta go.’

He was a fire warden on his floor and his last moments were spent helping people escape. His father knows this because Clyde Jr.’s boss told him so; Clyde Jr. had issued an order at 8:55 a.m. to hang up the telephone and get out. The boss, Clyde Sr. said, survived the planes and died of a heart attack a few days later.

‘Clyde was always a good kid with a big heart,’ the father said. ‘Except we always called him Kippy, seldom called him Clyde.’

Thirty years ago, the neighborhood kids in Harlem found it hard to believe he wasn’t related to the Knicks’ Walt Frazier, whose nickname, Clyde, was the signature of his urbanity. With a name like his, growing up when he did, why wouldn’t Clyde Frazier Jr. have embraced the game? He played a year at the state university in Albany before turning it into his prize avocation…

His good friend, whom he met in college, Dwayne Sampson, remembers how even as a student, it bothered Clyde Jr. that the women’s basketball program was minuscule compared with the men’s. ”Clyde helped organize intramurals for the women,” Sampson said. ”And then being involved in that aspect of the game became a way of life.”

In 1994, Clyde Jr. started a tournament for high school girls out of pocket in a tiny public school gym on 144th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard in Harlem. It was all in the neighborhood and all in the family. Clyde Sr. had gone to that school, P.S. 194. Before long, the Slam Jam Women’s Basketball Classic, operated by a nonprofit group called the Friends of Frederick E. Samuel Foundation, had grown to five events a year at places like St. John’s, Fordham and Riverbank State Park.

‘Started out mainly for inner-city girls, so college coaches could see them,’ Clyde Sr. said. ‘Then it became for teams from all over. One game, the gym would be all black. The next game, it would turn all white. My son loved that it was just about the game and helping these girls get to college.’

I promised Clyde senior that as often as I had the opportunity I would tell his son’s story on the anniversary of 9/11. I choose to remember a guy I never met who loved basketball and loved people. I honor his memory today.

Dr. J.